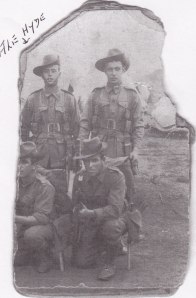

Alfred Joseph Hyde – John (bass)

Service number 248

Private 18th Battalion A company

Enlisted 15 February 1915

Embarked Sydney 25 June 1915 HMAT Ceramic

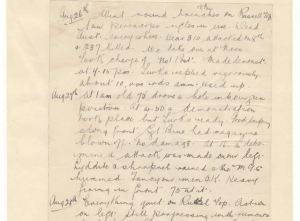

Joined MEF at Gallipoli Peninsula 16 August 1915

Wounded (gunshot wound leg and foot) 27 August 1915

To Anzac Base

Transferred to England, admitted King George Hospital Stamford St SE England 16 September 1915

Invalided to Australia 17 March 1916 per Ascanuis from England

Discharged 31 August 1916

Place of birth Eton, Windsor, Bucks, England

Occupation decorator

Appearance 5’71/4” dark hair, brown eyes

Age 21 years 11 months at enlistment

About the 18th Battalion

The 18th Battalion was raised at Liverpool in New South Wales in March 1915 as part of the 5th Brigade. It left Australia in early May, trained in Egypt from mid-June until mid-August, and on 20 August landed at Anzac Cove.

The battalion had not been ashore a day when it was committed to the last operation of the August Offensive—the attack on Hill 60—which lasted until 29 August and cost it 50 per cent casualties.

For the rest of the campaign the 18th played a purely defensive role, being primarily responsible for holding Courtney’s Post. The last members of the battalion left Gallipoli on 20 December. (AWM)

Interview with Mr Alfred Hyde, conducted by his grandson John (in 1975).

“I was 19 years old when I signed up in Sydney. I put my age up to 22 because I was afraid they wouldn’t take me, because they were very particular in signing up the first volunteers. There was a rush to volunteer in those days, young chaps were educated to being patriotic and to be able to go away and fight for your country and so there was no lack of volunteers. There was no doubt about it, the standard of young men that did join up was wonderful, their physique and everything else. We had ex-boxers, ex-swimmers, anything to do with physical sports, we had the cream of Australia. Men were enlisting in large towns all over Australia.

I enlisted pretty early in the piece, although I didn’t leave Australia in the first batch. They picked certain men out to the nucleus of the 18th Battalion that, so I was six months in Australia for that reason, because I had had previous military experience in England. I was in a volunteer regiment called the Buffs. We trained to be soldiers and before that as a boy I was in the Church Lads’ brigade in Eton.

We got six bob a day and there was deferred pay of a shilling a day and they kept that here and then you could make allotments to anyone you wished to so that they could draw your pay here if they liked.

After signing up we went up to Darlinghurst Barracks and had to undress and have a real physical check-up and then we were told what day to report and we were issued with our uniforms, no rifles. There were no rifles in those days, all we had was broomsticks, to use as a gun, to slope arms and present arms in parade duty. That was all we had. It wasn’t till a few months afterward that we were given rifles. We were trained at Liverpool, mainly hard physical training, marching and then parade formation and all that sort of thing and then rifle practice at the rifle butts. We also had bags stuffed with straw hanging off ropes for bayonet practice, and all exercises in using a rifle and bayonet. We were trained in what to do in combat and how to parry the enemy’s bayonet.

In comparison to British troops, our equipment, that is clothing, would have been a bit superior. We had no training in grenades. The first ones they used at Gallipoli were jam tin, empty jam tins, stuffed with bits of bread and dynamite and everything else thrown in. You had to light a wick and throw it quick and lively otherwise you would blow yourself up—and as a matter of fact some did do that. There were only a few men chosen to use the grenades, the same way that they hadn’t even formed a machine gun section before we went away so that when we got over there, a few men were taken from each battalion to make a machine gun crew. Most of the fighting we were involved in was primitive close combat with rifles and bayonets.

While we were still training we used to often put over a few ‘roughies’ to go on leave. I remember one very amusing time when my girlfriend’s uncle was in the battalion and I had been on leave for a week, and of course I was getting much of basic training, because I had had it before. So I came back from leave, when he was just going on leave so I said to him, ‘When you get down to Sydney send me a telegram saying that my girlfriend has had a re-lapse and to come at once !’ He sent the telegram and the colonel of the regiment was very concerned and he said to go at once. The colonel was a marvellous man. Colonel Chapman, he was a real soldier and a real man, and he did everything possible to keep the troops happy. Even going on the boat he had all sorts of competitions to keep everyone happy, boxing and the band, which was really beautiful, played all the time, he was a really wonderful man.

From the training area we went straight to the boat, ‘Ceramic’. We sailed on the troopship ‘Ceramic’ on the 25th of June, 1915. There was a tremendous crowd to see us off. Everyone was glad to be going because we didn’t know what we were getting into. On the boat we slept in hammocks, I preferred to sleep on the main deck. The boat was very crowded but the conditions were good. There were over 1000 men on board, a battalion and all the necessary troops to back it up.

We sailed, then we stopped at Melbourne, then around the Cape to Port Said: The weather was very hot going through the Red Sea and Port Aden. We weren’t allowed off the ship until we got to Port Said. And then on from there up to Alexandria and then overland in these ‘Cattle Trucks’ to Cairo and then we went to train in a place called Heliopolis, which was a suburb of Cairo. It was nothing like the old city of Cairo, it was a modern place with all high rise and all that sort of thing.

We fixed tents, all tents, with a ground sheet to lie on. It was terrifically hot in the day but very cold at night. We received more physical training, rushing all over the sand hills. It was mainly to harden us up than anything else.

The soldiers very often went into Cairo on leave. In one part of Cairo, which is the lowest place I’ve ever been, I know that once one of the soldiers caused a riot. What had happened I cannot explain but this chap was robbed of money in a brothel and one thing and another and he set fire to this place and there was a real riot on. He threw one of the Egyptians out of a window, I don’t know what happened to him. Tiny Ryan was his name and he was jailed.

At the end of training we were put on board the trucks and taken back to Alexandria. When we went on leave in Cairo, they were very poor most of the Egyptians, and they used to pester us a bit. In fact the British troops used to carry canes to brush them off with and they would say ‘Emshy Alla’- (get the hell out of it!!) They would fight among themselves in the street if you gave them money, trying to take it off each other and they would scream like girls. They were a funny sort of people.

We embarked for the Dardanelles from Alexandria. The main depot for the ships was Lemnos Island, the ships congregated there. We were drafted off the ship onto barges, I’d say about 30 feet long and 20 feet wide flat bottom barges and that was towed up to the beach as far as you could get it in and then you had to hop out of that and race onto the beach.

There were many troops other than the Australian where we fought. There were British troops, the Connaught Rangers, wonderful men, and the Gurkhas, troops from Nepal in India. They were only short stubby fighters, but in my opinion the best fighters on Gallipoli, fearless. They were trained by British officers in basic training but they were cleverer with their own weapons, knives they used to carry. They could cut your head off with one swipe, in fact they used to. They used to go out at night after these snipers and it was quite common for them to bring back the head of the snipers, holding him by his hair and bring him ‘in’. We were never short of cigarettes, we never had them but they pinched them from the Turkish Troops.

When our battalion arrived some trenches were already dug and also everyone had in their equipment an entrenchment tool, a kind of short shovel. So then we had to dig in ourselves as we advanced. We made about five or six of these advances before I was wounded.

We got the word ‘over the top’ and everyone charged like mad-men, some got excited and were firing even behind their own men. No-one was calm and it was a very excited scene.

When we arrived the others were well entrenched. The first lot that went ashore would have had it worse than what we had because they were being bombarded and sniped from all quarters. The main danger was the sniping. See the nature of the ground in Gallipoli was similar to the Blue Mountains here. You go over one section and then it’s a valley, then over another section. It was all rough country and you’re always going higher and higher. And in the distance was what they called the Anafarta Ridge. Where ever you looked you saw this big ridge in the distance. Actually no-body ever got over this ridge, although they got to the top and they could look down into the town below it. But our troops as a solid unit never got over there.

While we were advancing, all the time the British navy had all their warships bombarding this ridge and any other place which seemed likely to be concealing weapons or troops. That was another fearsome thing, because when a 16 inch shell bursts there would be a high flash and a great bang which would shake the ground under you.

The Turks had the biggest gun on Gallipoli, the ‘Big Bertha’ [ed ‘Beachy Bill’?] that caused more trouble than enough. They had it concealed behind some big ridge and they used to fire, and concentrate their fire from this gun – a big German gun. They could never silence that gun and it cost a hell of a lot of lives. I was at Gallipoli for a month or so. The withdrawal wasn’t till months after I had left. There wasn’t any medical treatment there, what they did when you got wounded was: the stretcher bearers would go up and collect you and bring you down to the beach, and they’d have all the stretchers lying on the beach ready for the orderlies from the hospital boats to come and get you. They put us on a boat donated by the New Zealand people and it was a beautiful boat. But they only took us to Lemnos Island. We were very disappointed when they put us onto a German boat that the navy had captured, a boat called the ‘Derrflinger’ which was a cargo, passenger boat. There were that many wounded that there were no beds, everyone was given a mattress, which were laid all along the decks. I was a stretcher case so that I wasn’t given a mattress, someone else got it for me: I was installed on the deck. No-body knew where we were going. We didn’t know it but we were going to England, and that was a nightmare trip. We went through the Aegean Sea and then the Mediterranean till we reached Southampton in England. But that was a nightmare trip because there were hardly any doctors or nurses, I don’t think there was a nurse, not one nurse, there were orderlies, that’s all, and there were people lying about with their wounds not being dressed, the food was rotten, there was hardly any food, a bit of bread and butter that was all.

The food we had at Gallipoli was ‘rough as bags’, because communications weren’t good. The only thing we had was a bit of Bully Beef and jam with a hard biscuit, about 2 or 3 inches in diameter and half an inch thick, so hard you couldn’t break it, you had to hit it with a rock to break it. And the flies, as soon as you put the jam on the biscuit, it was covered with flies, that’s why there was so much dysentery. The people that suffered most were the English troops, because not being used to the tropics they got this dysentery very bad. In fact I personally saw a couple of hundred of them just crawling on the ground unable to stand up.

When we got to Southampton there was a large train waiting for us and we got a wonderful reception from everyone and we were taken to London. I was the first Australian to go into a new hospital they had built, King Georges Hospital. This hospital was marvellous, modern, marvellous treatment, the food was fantastic. This hospital was run by the aristocrats of England, so there was no shortage of anything, although they were short of things throughout England. The hospital was supplied with everything, eggs, butter, cheese, bacon, everything.

After I was allowed to leave hospital I was sent to a convalescent home, a beautiful place but I was sick of it already. After being there for about a month I was allowed to go on leave and I went to my home in Eton. I wrangled about 3 times as much leave as I was meant to have but eventually I got word to report to Weymouth, in the south of England, to embark back to Australia.

While I was there I wrote to my eldest brother’s 0.C, he had joined the English regiment the Life Guards, a horse regiment, telling him I was from Australia and going back soon. My brother was in France and he had had no leave. The O.C. wrote back saying that he would be delighted to let him come. He arrived home and we had a marvellous time with him and all my old school friends.

Finally I had to come back and we were very well accommodated on a tourist ship. On the way back we called in at Durban in South Africa and the Dutch people gave us a wonderful reception at the town hall in Durban. With a show and beer laid on, in fact some of them made it a bit too hot and that stopped our leave for a few days.

When we got back to Australia we were warmly welcomed and most of us were taken to Randwick hospital where we were treated very well, but I was bored stiff with it all.

Later on when I was out of hospital they had this conscription campaign and they asked if anyone of us was willing to make a tour of the country. I was sent out west to Wellington, Dubbo, and Bathurst all expenses paid.

There was a good deal of hostility towards conscription, but that had nothing to do with me. My job was to give my account of the fighting on Gallipoli and army life generally. I was welcomed into the towns and meetings were arranged in the town halls. The people were very generous in putting me up in their private homes and my tour was pretty successful. But as everyone knows the conscription campaign failed. I personally think it was a good thing, because the cream of Australia had already gone and if many thousands more had left it would have been a very sorry day for Australia.

I got out of the army then as soon as I could because I didn’t want to be going from one hospital to the next so I got them to discharge me. But I still had to report to Randwick hospital occasionally for years after for treatment. That was August 1916, I was a private when I was discharged. I was offered Sergeants rank but I wanted to go on leave and go out and see things so that I didn’t accept the offer and I became a civilian.’